John Ruskin and Chamonix: Beyond the “Pierre à Ruskin”

Ruskin’s Stone: A Franco-British Legacy Beneath the Brévent

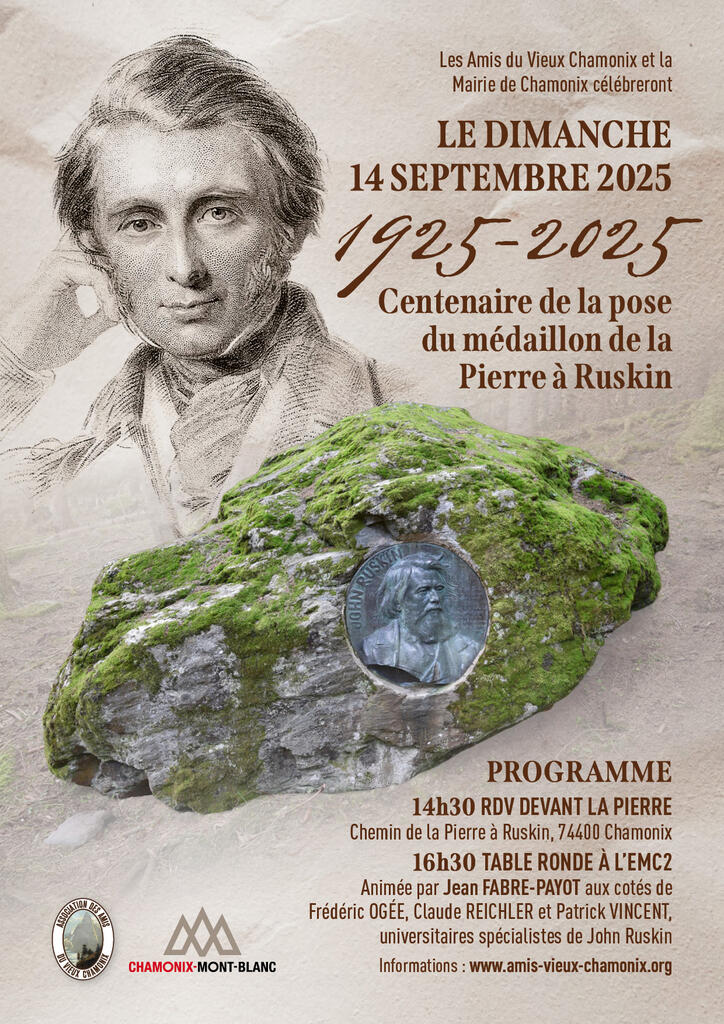

Hidden beneath the cliffs of the Brévent lies an erratic boulder, a vestige of ancient glaciers, known as “Ruskin’s Stone.” At first glance, it seems ordinary, yet it carries a remarkable story : the deep cultural connection between the Chamonix valley and Britain.

In 1925, the stone became the stage for an official tribute. French and British dignitaries gathered there to unveil a bronze medallion honoring John Ruskin, the leading Victorian thinker, art critic, and writer whose ideas and words profoundly shaped generation’s perception of nature, art, and the Alps.

Ruskin, an intellectual captivated by Chamonix

In Britain, Ruskin is considered one of the great minds of the 19th century—Marcel Proust even ranked him alongside Tolstoy, Nietzsche, and Ibsen. His major works, including Modern Painters, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice, influenced both art and social thought. Yet few remember how much Chamonix inspired his writing.

He first discovered the valley at the age of 13 and returned no fewer than 18 times between 1833 and 1888. In Modern Painters, he composed some of his most lyrical passages on the glory of mountains. For locals, however, he was also remembered as the solitary walker who, after dinner, watched the sunset over the Aiguilles from his « big old stone beneath the Brévent», later known as Ruskin’s Stone.

A mountaineer before a sage

The image of an elderly scholar contemplating the peaks tells only part of the story. As a young man, Ruskin was a vigorous mountaineer, guided by Joseph-Marie Couttet. He would set off at dawn, cross ridges and glaciers, and return late at night, exhausted but exhilarated. “I know I can walk with the best guides and wear out the bad ones,” he proudly wrote in 1844.

This physical immersion was essential to his vision of the Alps: partly scientific, inspired by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure; partly artistic, shaped by Turner; and partly spiritual, drawn from the Bible. It was this synthesis that transformed the Alps in the European imagination—from a hostile wilderness of rock and ice into a landscape of beauty, moral elevation, and inspiration for generations of British travelers.

A symbol that endures

Nearly two centuries later, Ruskin’s Stone remains a symbol of that cross-cultural encounter: a reminder of how a young Englishman’s passion for the mountains helped forge Chamonix’s place in the imagination of Victorian Britain.

For Ruskin, Chamonix was never just a destination. It was the landscape that shaped his soul—and gave him the very language to express the grandeur of nature.